Lichens: The Cosmic Travelers of Our Galaxy

Written on

Chapter 1: The Intriguing Concept of Panspermia

Lichens, often dismissed as mere stains on rocks, could hold the key to a fascinating concept known as panspermia. This idea suggests that life may travel from one planet to another, possibly even from star to star. If this theory holds true, it implies that our galaxy might be teeming with life, perhaps originating from just a single source. Imagine realizing our Star Trek fantasies, where life exists beyond Earth! Until recently, however, we lacked a credible organism that could withstand the harsh conditions of space travel and thrive on another world. That is, until lichen entered the scene.

So, what makes lichens such promising candidates for panspermia? The answer lies in their unique symbiotic relationships and the extraordinary capabilities that emerge from them. Early biologists found lichens perplexing because they seemed to embody traits of plants, bacteria, and fungi all at once. It wasn't until Simon Schwendener's groundbreaking discovery in 1868 that we learned lichens are composite organisms comprised of fungi and algae or cyanobacteria. His insights faced skepticism initially but were ultimately validated, reshaping our understanding of these remarkable life forms.

Section 1.1: The Superpowers of Lichens

The symbiotic relationship between fungi and algae yields astonishing emergent properties. Just as metals and fuels can be combined to create vehicles with unique functionalities, fungi and algae collaborate to develop extraordinary abilities that neither could achieve alone. These abilities include resilience to radiation, the capacity to endure complete dehydration, and tolerance to extreme temperatures and high G-forces. Over millennia, this partnership has evolved, making lichens some of the toughest organisms on the planet.

Consider this scenario: a piece of lichen clings to granite rock and is struck by a meteorite, sending it hurtling into space. Surprisingly, studies show lichens could survive such extreme conditions. In one 2007 experiment, researchers subjected lichens to shockwaves mimicking a meteorite impact, and they withstood pressures of up to 45 GPa, which is equivalent to balancing 1,200 blue whales on one’s head! Their survival is nothing short of remarkable.

This video provides a comprehensive guide on the potential of lichens in space, revealing how these organisms could thrive even in the harshest conditions.

Section 1.2: Surviving the Harshness of Space

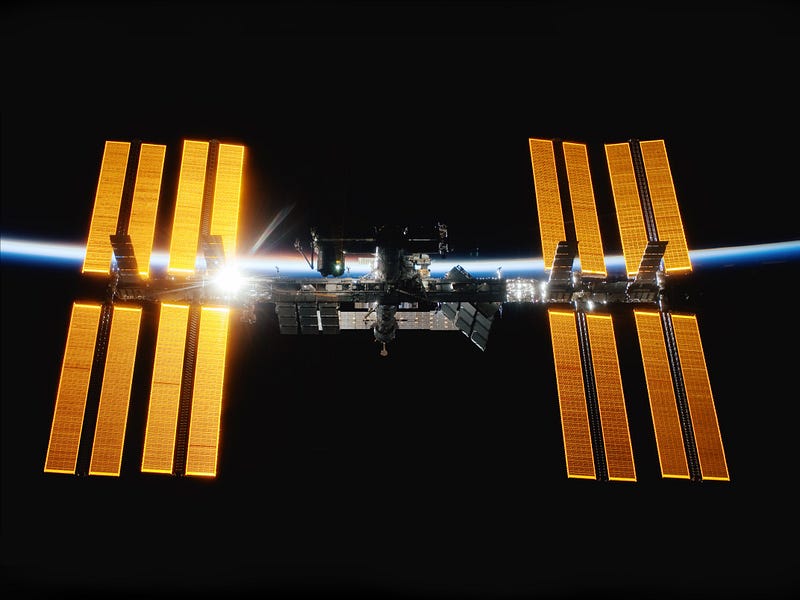

In a separate study in 2005, scientists exposed lichen samples to the vacuum of space by attaching them to the International Space Station (ISS) for 15 days. Astonishingly, all samples survived, enduring extreme temperature fluctuations and intense UV radiation. In contrast, the well-known tardigrade, known for its resilience, did not fare as well under similar conditions, with a third of its population succumbing to the harshness of space.

However, the real challenge lies in landing. A 2010 study tested lichens by exposing them to the extreme heat of re-entering the Earth's atmosphere. Unfortunately, they did not survive the intense temperatures. This raises an interesting question: could lichens survive embedded within a larger meteorite, which would provide insulation during atmospheric entry?

Chapter 2: Potential for Interplanetary Travel

This video dives into the fascinating dynamics of lichen survival and their potential for interplanetary colonization.

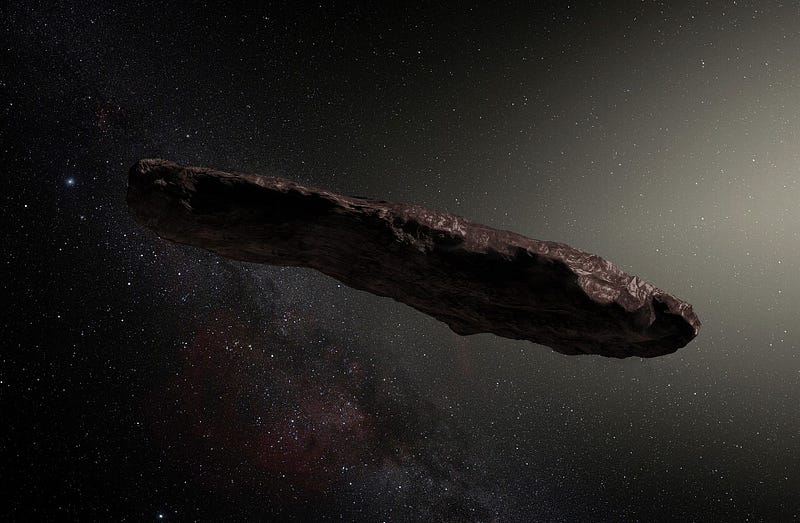

For lichens to truly embark on a journey through space, they would need to be encased in a larger body to protect them from heat during re-entry. Theoretically, as smaller meteorites collide and merge in space, they could trap lichens within their cores, allowing them to survive an impact on another planet.

Yet, such events are exceedingly rare. Should a lichen-laden meteorite venture towards another planet, it would require a low-speed impact to ensure survival. Despite the improbability, the possibility remains tantalizing.

Section 2.1: The Potential for Terraforming

Lichens are not merely composed of one fungus and one alga; they can include multiple fungi and various species of algae, cyanobacteria, and bacteria. This diversity allows them to function as self-contained ecosystems that can separate and colonize new environments effectively.

Once landed on a new, barren planet, lichens could initiate a process of terraforming. Fungi might begin breaking down rock to create soil, while algae could thrive in water bodies, oxygenating the atmosphere. Over time, these simple life forms could lead to the development of complex ecosystems similar to those on Earth.

This raises an intriguing question: has this process already occurred? Studies from 2010 indicate that lichens could survive Martian conditions, thriving in simulated environments mimicking the planet's atmosphere. With recent discoveries of liquid water on Mars, it’s plausible that lichens may be capable of colonizing the planet.

While Mars's thin atmosphere may facilitate atmospheric entry for lichens, no one has yet tested this theory in practice. The fossil record shows lichens have existed for around 250 million years, encountering numerous meteorite impacts during that time, suggesting they may have traveled to other planets long ago.

In conclusion, while it may be improbable that lichens currently thrive on Mars, the tantalizing possibility remains. They could be the first Earth organisms to have made their way to another world.

Section 2.2: The Limits of Interstellar Travel

However, the dream of interstellar panspermia faces significant challenges. Lichens, with their limited lifespan of up to 5,000 years, struggle to endure the extensive journey required to reach planets like Proxima Centauri B, which is over 4 light-years away. To arrive there within their lifetime, they would need to travel at speeds far beyond our current capabilities.

In summary, while there is a very slim chance that Earth-originating lichens might inhabit Mars, the dream of them reaching other star systems remains firmly in the realm of speculation. So, the next time you encounter those curious yellowish-green stains on a rock, remember: they are tiny biological vessels with the potential to terraform new worlds, contingent upon a perfect meteor impact and a bit of luck.